aka “Long Liz”

The Third of the Canonical Five Ripper Victims

September 30th, 1888; Berner Street, Whitechapel

Dr. Thomas Barnardo was well known in Whitechapel as a servant to the poor. With a background as a doctor, Barnardo had become a street minister and also went on to open a famous house for impoverished young boys. On September 26th, 1888, Dr. Barnardo was visiting the lodging house at 32 Flower and Dean. There was a group of women sitting in the lodging house kitchen, looking “thoroughly frightened” and talking about the Whitechapel murders.

Dr. Thomas Barnardo was well known in Whitechapel as a servant to the poor. With a background as a doctor, Barnardo had become a street minister and also went on to open a famous house for impoverished young boys. On September 26th, 1888, Dr. Barnardo was visiting the lodging house at 32 Flower and Dean. There was a group of women sitting in the lodging house kitchen, looking “thoroughly frightened” and talking about the Whitechapel murders.

One woman sat at the table crying. “We’re all up to no good, no one cares what becomes of us! Perhaps some of us will be killed next.”

Several days later, Barnardo identified Liz Stride’s body as one of the women who had been present in the lodging house kitchen for that foreboding conversation.

Early Life and Background

Records of Elizabeth Stride are spotty at best, with many gaps in her story and some misleading falsehoods. Most of what is known about her is from public records as well as the relatively sparse inquest testimony of the few people who were close to her.

Records of Elizabeth Stride are spotty at best, with many gaps in her story and some misleading falsehoods. Most of what is known about her is from public records as well as the relatively sparse inquest testimony of the few people who were close to her.

The Ripper’s third victim was born Elisabeth Gustafsdotter on November 27, 1843. Her parents were Gustaf Ericsson and Beatta Carlsdotter, Swedish farmers living on a farm called Stora Tumlehed near Gothenburg. Elisabeth moved to Gothenburg city in 1860, in domestic service of a man named Lars Olofsson. By the time 1865 arrived, she had fallen on some hard times, and the police registered her as a prostitute. She gave birth to a stillborn baby girl on April 21 and later that year was also treated twice for venereal disease and infection.

On February 7th, 1866, Elizabeth applied for a transfer to the Swedish parish in London, and in July is logged in the London registry as an unmarried woman. Her later paramour, Michael Kidney, went back on forth as to why she had come to London in the first place. First he had said that it was “to see the country” but later claimed that she came over as a domestic servant. Interviewee Charles Preston corroborated the second opinion, and said that she came from Sweden in the service of a “foreign gentleman”.

Elizabeth married John Stride on March 7, 1869 at the age of twenty-six. They moved to East India Dock road. The two operated a coffee shop together on Poplar, moving from their first location to another one on the same street. In 1875, the business was taken over by a man named John Dale. Little is known about the Strides’ marriage aside from their co-ownership of the coffee shop. Kidney said that Elizabeth claimed to have given birth to nine children in her life, but there are no surviving records of the children born from the Strides’ marriage.

Separation from John Stride and Final Years

In 1878, a saloon steam ship called the Princess Alice crashed into the Bywell Castle steamer on the Thames River. Between 600 and 700 people were killed in the disaster. When asking for financial assistance at the Swedish Church in 1878, Stride claimed that the accident had killed her husband and children and that she had also suffered an injury to her palate while struggling to escape. Investigators have determined that this was a complete fabrication, though; in fact, John Stride actually was alive and well in 1878 and did not pass away until dying of heart disease in 1884.

This lie would lead us to believe that Elizabeth was having troubles in her marriage that led to a separation from her husband. In that case, she used the Princess Alice story to cover up her separation and to garner more sympathy so that the church would give her more money. Regardless of Elizabeth’s deceit, the clerk of the church, Sven Olsson, remarked to the inquest that at the time she had been in ‘very poor’ circumstances. The last time Elizabeth was listed in a census as living with her husband was 1881, but after that they no longer lived together.

From then on, “Long Liz”, as she was known around Whitechapel, split her time between different workhouses and lodging houses. From December of 1881 through January of 1882, she was treated for bronchitis in the Whitechapel Infirmary, and then went straight into the adjoining Whitechapel Workhouse. She continued to char and made some money sewing as well. Stride, like Chapman, was likely just a “casual” prostitute, only soliciting when she was really hard up for money for a bed for the night and needed a quick three pence.

Another way that Liz procured funds was by borrowing it from her on-again off-again lover, Michael Kidney. She lived with him on and off as well, at his home on Devonshire Street. His is one of the addresses that she reported to the Swedish Church in addition to several lodging houses in the area. The two had a tumultuous relationship, and Elizabeth would often live apart from Kidney in lodging houses for several days or weeks before returning.

All that is really known of the relationship between Kidney and Liz Stride is from police records and from Kidney’s testimonies at the inquest. Kidney claimed that the reasons for her disappearances from his home were due to her drinking benders. Long Liz did, in fact, appear before the Magistrate court eight times for drunk and disorderly conduct in the two years leading up to her death.

“It was the drink that made her go away,” Kidney told the inquest. “She always returned without me going after her. I think she liked me better than any other man.”

Compounded with her troubles with booze, however, is the fact that there was likely physical abuse in the relationship. Domestic abuse was rampant in Victorian Whitechapel, and Liz did charge Kidney with assault in 1887. She failed to appear at the Thames Magistrate Court, however, and the case was dropped.

Stride’s Last Known Activities and Witness Testimonies

From Wendesday September 26th through her death on the morning of the 30th, Liz had been staying at the lodging house at 32 Flower and Dean Street. A fellow lodger, Catherine Lane, testified that Elizabeth told her she had “had words” with Kidney and that was her reason for staying at the lodging house. During her time there, she made money from the house deputy, Elizabeth Tanner, by cleaning rooms. On the day of her death, she had earned six pence for cleaning two rooms of the lodging house, after which she went out.

Stride’s story is the most populated with potential witnesses of any of the other victims. It is also one that caused the most confusing detours, due to the fact that it is very likely there was a second couple on the street the evening of Stride’s death.

Elizabeth Stride is seen in the company of a man

Newspapers reported a story told by two laborers that were not interviewed during the inquest, J. Best and John Gardner. The two said they saw Elizabeth Stride at about 11 pm as they were entering a pub on Settles Street called the Bricklayers’ Arms. She was in the company of a man who was about five feet, five inches tall. They said that he had a thick black mustache with no beard and was wearing a morning coat and billycock hat.

The two found him to be respectable looking, and so were surprised to see that he and the woman were shamelessly hugging and kissing near the doorway of the pub. After unsuccessfully trying to get the man to come in with them for a drink, they said to Stride, “That’s Leather Apron getting ‘round you!” After that, they said, the couple was “off like a shot” away from the pub.

Forty-five minutes later, William Marshall was standing on his doorstep at No. 68 Berner Street, between Christian and Boyd Streets. Across the street, he saw a woman that he claimed was Stride talking to a man that Marshall described as a stout man of about five feet, six inches tall wearing a black cut-away coat, dark trousers, and a cap that was “like something a sailor would wear.” As he walked by, he heard the man say, “You would say anything but your prayers,” at which the woman laughed. Marshall said that the man looked to be educated and had “the appearance of a clerk” during the inquest.

The next testimony came from PC William Smith, and was regarded as one of the more reliable ones both by the inquest. Smith saw Stride with a man in Berner Street at 12:35 am, across the street from the International Working Men’s Educational Club. PC Smith said the man had a dark complexion and a dark moustache, wearing a cutaway coat and dark trousers and carrying a parcel wrapped in newspaper. Smith described the man as looking “respectable” and both the man and the woman looking sober. He also took note of the rose she was wearing on her jacket, which matched the one that was discovered on Stride after her death.

Sometime between 12:40 and 12:45, a dockworker named James Brown was coming from Fairclough and Berner Street. He saw a man and a woman standing at the corner, the man with his arm up against the wall and the woman with her back to it. He only glanced at the man and so could not describe anything but the long black coat he was wearing. He heard the woman say, “No, not tonight. Some other night.” Brown did not see a flower pinned to the woman’s jacket, indicating that this may have been a different couple.

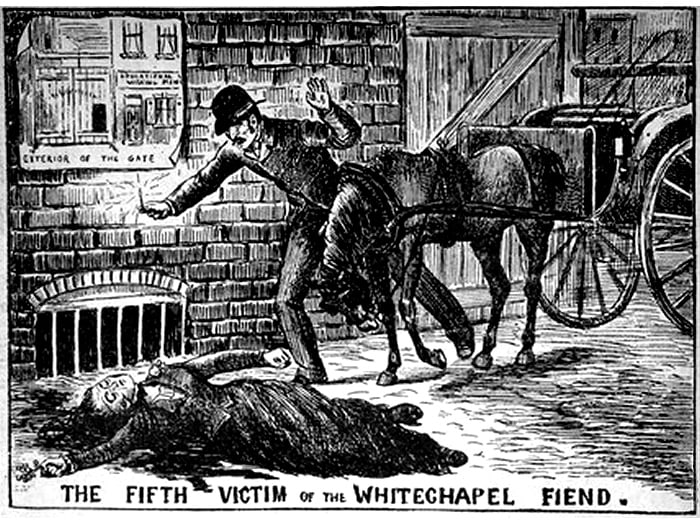

One of the most sensational witness testimonies came from a recent immigrant named Israel Schwartz. He spoke very little English, and happened to be turning into Berner Street from Commercial Road around 12:45 am that evening. He was across the street from the gateway where Stride’s body was found and saw a man speaking with a woman standing nearby. He saw the man try to pull the woman into the street. When she resisted, he threw her to the ground, and Schwartz crossed to the opposite side of the road. Upon crossing, he saw a man lighting his pipe, and he heard the first man shout: “Lipski.” Schwartz continued walking, but saw that the second man was following him and ran away. He was unsure of whether the two men were together or knew each other, but he was able to identify Stride’s body at the mortuary as the woman he saw.

Berner Street circa 1909. This photo shows the street looking much the same as it did during the time of Stride's murder in 1888. Her body was found just inside the entrance to Dutfield's Yard, which was located just below the wagon wheel seen in this photograph.

The man who had assaulted the woman had been about five feet, five inches tall with dark hair and a small brown mustache. Schwartz said that he had a full face, was broad shouldered, and wearing a dark jacket and trousers with a peaked cap. For unknown reasons, Schwartz was not present at the Stride inquest. Perhaps police believed that, due to the lack of bruising on Stride’s hands and knees consistent with being thrown to the ground, Schwartz had actually seen someone else. Otherwise, police may have been concerned that reporting a shout of “Lipski” would implicate Jewish people in the murder and cause public backlash against them. Whatever the reason, Schwartz’s testimony endures because the Star newspaper reported it on October 1.

A nearby resident, named Fanny Mortimer, supports the idea that there was a different couple on the street during the time Stride was murdered, which could explain inconsistencies between the witness reports. She reported hearing a commotion outside at the Socialist Club and going out to investigate. After hearing about Stride’s murder, she questioned a “young man and his sweetheart” standing on the nearby corner, but they had heard nothing.

Mortimer was convinced that she had seen the murderer, because the only man she saw pass on the street coming from the direction of the Socialist Club was a man carrying a shiny black bag. The man with the black bag later reported himself to the Leman Street Police Station after reading Mortimer’s account in the paper. His name was Leon Goldstein, and he was ruled out as a suspect.

Examining the Injuries

Two distinct elements make Stride’s murder unique among the canonical five. First, there were no mutilations to her abdomen in the way that there were on the bodies of the other four victims. Second, the cause of death was not determined to be strangulation, as there were no marks of strangulation on her body.

There had been some criticism of how police had handled the Annie Chapman investigation. Men from the medical community, for example, complained that it was a failure to have just used one doctor for the autopsy without getting a second opinion. For that reason, both Dr. Phillips and Dr. Blackwell conducted Elizabeth Stride’s autopsy.

Liz was found in possession of two pocket-handkerchiefs, a thimble and a piece of wool attached to a card. A red flower was pinned to the dark jacket she wore. She was also found clutching a package of cachous, which were used to sweeten the breath. These cachous were still in the package and not scattered around, as they would have been if she had been suddenly knocked to the ground.

Dr. George Phillips and Dr. Frederick Blackwell agreed that the cause of death was blood loss from the left carotid artery due to the wound on her throat. The gash to the throat was consistent with the wounds of the other Ripper victims, including a clean, deep knife wound of about 6 inches that moved from left to right. Some have speculated that it is possible the murder could have been performed with a different knife, specifically a shoemaker’s knife, than the previous two. In fact, doctors conceded that this was a possibility; however, it is also possible the same weapon used on Nichols and Chapman was used on Long Liz.

Puzzlingly, though, Dr. Phillips and Inspector Reid mentioned in their reports that there was no sign of blood spatter that would indicate she had been killed while standing. In fact, PC Lamb indicated in his testimony that, “She looked as if she had been gently laid down.” Phillips claimed there was no trace of malt liquor, anesthetics, or narcotics in Stride’s stomach. Therefore, drugging or drunkenness cannot account for Stride having gone down without a struggle.

According to Dr. Blackwell:

There was a check silk scarf round the neck, the bow of which was turned to the left side and pulled tightly. I formed the opinion that the murderer first took hold of the silk scarf at the back of it and then pulled the deceased backwards.

An alternate theory regarding Stride’s cause of death was presented by Bill Beadle in The Journal of the Whitechapel Society as something called RCA. This stands for Reflex Cardiac Arrest and occurs when a subject dies due to a sudden pressure to major arteries on the neck. This occurs more commonly in victims who are drunk or extremely frightened. With fewer forensic resources than modern investigators, this conclusion would have been impossible to determine in 1888.

Some believe that the Ripper did not kill Elizabeth Stride at all, due to the differences between her injuries and those of the other victims. It is also possible, however, that the Ripper was merely interrupted by the arrival of Louis Diemschutz and his pony, and for this reason he was compelled to claim a second victim on the evening of the Double Event.

For more on what transpired during the early morning hours of September 30, 1888, please see our article on “The Double Event“.

A Lonely Burial

Due to Stride’s limited social network, she took the longest to identify. She was identified by the end of the week and laid to rest that following Saturday, the sixth of October, at East London Cemetery, Plaistow, London, E 13.

No friends or family were available to lay Stride to rest. The undertaker, Mr. Hawkes, paid for a small funeral with funds from the church.

Elizabeth Stride's Grave in the East London Cemetery

Her grave, no. 15509, can still be seen today.

Sources- Reinvestigating Murder: How Did ‘Long Liz’ Die? – by Bill Beadle (originally appeared in The Journal of the Whitechapel Society)

- Anything but Your Prayers: Victims and Witnesses on the Night of the Double Event – by Antonio Sironi and Jane Coram (originally appeared in Riperologist No. 66, April 2005)

- Casebook: Jack The Ripper, Victims: Elizabeth Stride

- A Complete History of Jack the Ripper; Chapter 10 – by Philip Sudgen