aka “Dark Annie”

The Second of the Canonical Five Ripper Victims

September 8th, 1888; Hanbury Street, Spitalfields; 5:30 am

As the nearby brewery clock struck 5:30, Elizabeth Long, also known around Whitechapel as Mrs. Durrell, was walking along Hanbury Street when she passed a man and a woman standing against No. 29. The man’s back was to her so she couldn’t see his face, but he was dressed in a long black coat and was wearing, according to Long, a deerstalker hat.

As she passed, she heard the man say, “Will you?”

The woman, whom Long later identified as Annie Chapman, replied, “Yes.”

5:15 am, a young carpenter who lived at No. 27 Hanbury Street named Albert Cadosch went out into his backyard, probably to use the lavatory. He reportedly heard a woman’s voice say “No,” and a sound of something falling against the fence connecting the backyards of No. 27 and 29.

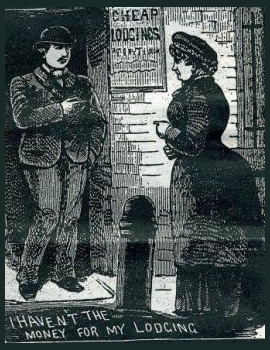

Jack the Ripper portrayed wearing a deerstalker hat and long overcoat

At 6 am, John Davis, the occupant of No. 29 Hanbury Street, prepared to go to his job as a carter for the day. His apartment was at the front of a three-story building that housed multiple families. It had a small backyard that easily connected to Hanbury Street via a 20-foot passageway, which meant that trespassers – including prostitutes and their clients – were frequent nuisances to the seventeen residents of No. 29.

29 Hanbury Street, Spitalfields

29 Hanbury Street Passageway

When he descended the stone steps into the backyard of No. 29, he was met with a mutilated female body sprawled between the steps and the neighboring fence.

He noticed that her skirts were pulled up to her groin and, without further investigation, ran into the neighboring street to call for help. He flagged down three workmen, James Green, James Kent, and Henry John Holland, who took one look at the body and then rushed out to find a constable.

They soon came upon Inspector John Chandler of H Division on Commercial Street

“Another woman has been murdered,” they told him.

Annie Chapman’s Family Life and Loss

The victim was another Whitechapel prostitute by the name of Annie Chapman. To her friends, she was known as Dark Annie.

Annie was born to a George Smith and Ruth Chapman and had three sisters. In 1869, she married John Chapman at the age of 28. John worked as a coachman and in other service positions.

Annie and John Chapman circa 1869

They had three children: Emily Ruth, Annie Georgina and John Alfred. A happy family life was not in the cards for the Chapman’s, however. Emily Ruth died of meningitis in 1882 at the age of 12 and John Alfred was born disabled and surrendered to a charity school for care.

Possibly due to these tragic strains on their marriage, both John and Annie Chapman became heavy drinkers. Annie was arrested several times for public drunkenness in Windsor, and a police report blamed her “drunken and immoral ways” for the end of the Chapman’s’ marriage around 1884 or 1885. John was no teetotaler himself, however, and soon died on Christmas of 1886 of cirrhosis of the liver and dropsy.

Despite their earlier estrangement, Annie was hit hard by the loss. Annie’s friend Amelia Palmer said that after John’s death, even until she died, “she seemed to have given away all together”. Annie Georgina was rumored to be traveling in a performance troupe in France in 1888, leaving her mother, for all intents and purposes, without close family.

Annie’s Final Years in Whitechapel

Before John’s death, Annie lived a modest existence, but had not engaged in prostitution. She received ten shillings a week from John Chapman and supplemented that allowance by selling crochet-work and flowers. At the time of John Chapman’s death, Annie lived with the sieve maker called John Sivvey and sometimes “Siffey” (accounting for another of Annie’s names — Annie Siffey — as well). John Sivvey left Annie soon after John Chapmen’s death, presumably because of the loss of Annie’s weekly allowance, and moved to Notting Hill.

After this further shake-up, Annie continued to sell her wares, while scraping by with the help of some begging and prostitution.

Crossingham's Lodging House, 35 Dorset Street, Spitalfields.

The lodging house (its entranced marked by the woman in the doorway) is just opposite the entrance to 13 Miller's Court.

Annie spent much of her time living in different lodging houses in the Whitechapel district. In addition to living off her small crochet earnings, Annie was often provided with a nightly bed at Crossingham's Lodging House on Dorset Street by a man named Ted Stanley. At first, the police only knew Stanley as “The Pensioner”, because witnesses from the lodging house were unsure of his identity. He claimed to be a former military man who got his earnings from an army pension. During Stanley’s inquest on September 14th, however, it was revealed he was actually not in the military, but worked as a bricklayer.

In the days before her fatal encounter with the Ripper, Annie was having her share of difficulties. Around the end of August, she got into a fistfight with fellow Crossingham's lodger, Eliza Cooper. Though some people in the lodging house claimed it was in a fight over Ted Stanley, Cooper testified in the inquest that they had tussled over Annie’s failure to return a bar of soap. According to Cooper, Annie had borrowed the soap to lend to Stanley; after a few days of Eliza asking for it back, Annie had tossed her a half-penny and told her to “go get a half-penny’s worth of soap.” Eliza claimed that she had struck Annie in the face and chest during a fight at the Britannia Public House.

Others commented that Eliza had been the one to steal from fellow lodger, Harry the Hawker. Annie had called Harry’s attention to the sleight, instigating a fight between the two women. Amelia Palmer told police that the actual fistfight had taken place later at the lodging house rather than at the pub.

It isn’t certain whose story is accurate. Crossingham's Lodging House deputy, Timothy Donovan, however, referred to Annie as generally quiet and inoffensive and that this was the only disagreement he knew of her having with another lodger. Regardless of who was at fault, Annie sustained injuries that remained evident during the post-mortem, requiring police to investigate Eliza Cooper’s story. Donovan confirmed to police that Annie had shown him the black eye she had gotten during the fight on August 31st.

Annie may also have spent time in the casual ward before her death, a place where the poor of Whitechapel could go when they were ill. Though there was no record of her being there, she had told her friend Amelia Palmer on September 4th that she was planning to go there for a couple of days. After her death, Donovan found medicine in her room. Pills were also found on her person when her body was discovered at No. 29 Hanbury Street.

On the evening of the 7th, she was in the lodging house kitchen “not the worse for drink,” according to fellow lodger William Stevens. Annie sent Stevens out for a pint of beer and they drank it together around 12:30 am. She then went out, and returned to the lodging house kitchen with a potato to eat around 1:30 am. Donovan, the house deputy, inquired about the money required for her room, and she let him know she did not have it, but to hold her bed for her.

“Never mind, Tim,” she said, “I'll soon be back.”

Stevens reported that Annie had come to the lodging house kitchen carrying a box of pills, a bottle of medicine and a bottle of lotion, but that the box of pills had fallen apart. She took a corner of an envelope from the mantelpiece and put two of the pills inside. Then, around 1:50 am, she went out again. She was not seen by anyone who knew her until her body was discovered at 6 am.

The Crime Scene and the Body

By the time the Inspector Chandler arrived, a crowd had gathered in the passageway at No. 29 Hanbury Street, trying to get a glimpse of the body. Inspector Joseph H. Chandler was on the scene by 6:10 and sent for Dr. George Bagster Philips, who was there 20 minutes later.

The backyard at 29 Hanbury Street

Annie Chapman's body was found next to the fence, just by the steps.

Annie Chapman’s body was mutilated even more than Polly Nichol’s had been. She had a similar cut across her throat that moved from left to right, as well as a gash in her abdomen made by the same knife. Chapman’s intestines were torn out and placed on the ground over her right shoulder, though still connected to her body. She was also missing her uterus and parts of her bladder and vagina.

Mortuary photo of Annie Chapman

The doctor was so disturbed by the damage done to Annie’s corpse that he refused to go into explicit detail about the abdominal mutilations during the inquest. His description is as follows:

The left arm was placed across the left breast. The legs were drawn up, the feet resting on the ground, and the knees turned outwards. The face was swollen and turned on the right side. The tongue protruded between the front teeth, but not beyond the lips. The tongue was evidently much swollen. The front teeth were perfect as far as the first molar, top and bottom and very fine teeth they were. The body was terribly mutilated…the stiffness of the limbs was not marked, but was evidently commencing. He noticed that the throat was dissevered deeply; that the incision through the skin were jagged and reached right round the neck…

The fact that Annie’s tongue was found protruding from her mouth implied that she, like Polly Nichols, had died from asphyxiation rather than from the damage done by the killer’s knife. The autopsy revealed indications found in the lungs and membranes of the brain of advanced disease. In fact, from the state of her lungs, investigators speculated that had she not been murdered on the 8th of September, she would soon have died of tuberculosis. In spite of the fact that she was described as “plump”, her body also showed signs of starvation. There was a little food in her stomach, but no alcohol in her system, which eliminated the possibility of her having spent those missing four hours in a public house.

The crime scene seemed to imply that Annie did not put up much of a struggle. Even Cadoche, who presumably heard Annie and her murderer from the adjoining backyard, described a limited amount of noise coming from the yard of No. 29. It is possible, however, that in her sickly state, and so taken by surprise by the attack, and she did not have the opportunity to cry out before being stifled.

Additionally, Annie’s belongings had been scattered across the backyard of No. 29, a fact that has baffled students of the case for over a century, starting with investigators. Dr. Philips said that Annie’s belongings had been placed near her body in order, “that is to say arranged there.” These belongings included a piece of muslin, an envelope corner containing two pills, and a comb wrapped in paper. Abrasions on her fingers showed that she had been wearing three rings, apparently of brass, but those had either been pawned or taken by the murderer. She was also wearing a kerchief around her neck, which she had been wearing when she left the lodging house.

Press also claimed that two farthings were found in the yard, though this is not stated in police reports. In spite of many scholars believing the farthings to be a press fabrication, the mysterious farthings have remained the source of speculations as to the Rippers identity and possible affiliations.

The envelope with the two pills was found on the ground, and there were considerable efforts on the part of investigators to find the sender. The envelope was stamped with the seal of the Royal Sussex Regiment, and the letters “M”, “S”, and the number “2” were visible on the envelope. Police followed this potential lead to the Regiment, and came up empty-handed. Afterward, William Stevens came forward to how the envelope had been a random find inside the boarding house rather than actual correspondence.

A few drops of blood were visible on the fence above Annie’s head, but not as much as to suggest that her throat had been cut while she was still living. Remarkably, a nearby water spigot showed no signs of having been touched by someone whose hands were covered in blood, a further sign of the Ripper’s audacity.

Also found on the scene was a leather workman’s apron, which led to the arrest of a villainous figure in Whitechapel, known as “Leather Apron”, really named John Pizer. The apron was later found to belong to a resident of No. 29, and Pizer was released after his alibis were confirmed.

Discrepancies in Witness Testimony

Several questions arose at the initial discovery of the body as well as during the inquest as to a) where Annie had spent her final hours and b) what exactly was the time of death. Dr. Philips noted that, though rigor mortis had not set in at the time the body was discovered, the body was quite cold. This led him to postulate that the time of death had been at about 4:30 am.

His estimation ran in direct opposition to the testimonies of three witnesses. Mrs. Long expressed certainty that she saw Annie at 5:30 am, due to the chiming of the nearby brewery clock. Police were inclined to believe Mrs. Long’s testimony, due to the fact that she was able to identify Annie’s body in the mortuary.

Albert Cadosch was also certain that he had heard the voices coming from the backyard of No. 29 around that same time. If either of these two witnesses were incorrect, it would make the possible identification all the more impossible.

The biggest case for Dr. Philips being in error came from John Richardson. On his way to work, he stopped in the backyard of No. 29 to sit on the steps and remove a broken piece of leather from his boots. He was sitting on the back steps that would have been about a foot away from Annie’s body, had she been murdered at 4:30 am. However, Richardson reports not having seen anything out of the ordinary.

One reason that was given for the coldness of Annie’s body was the level of mutilation to her abdomen. Exposure of so many veins, arteries, and internal organs to the cold morning air could have hastened the chilling of the body at a higher rate than that of an intact corpse.

The other option would be that the witness testimony was inaccurate, a case that many have made, including Scotland Yard at the time. There is first the obvious discrepancy between Cadosch and Long’s stories. For both of them to have actually heard and seen the victim, one of the witnesses would have to be off by 15 minutes or so, either due to confusion or deception.

There is also a question as to whether or not it was actually Annie Chapman that Mrs. Long had seen on Hanbury Street, since she had never seen the woman prior to the morning of the 8th and did not see the body in order to identify it until four days later on the 12th of September.

Additionally, the official position of Scotland Yard was to treat John Richardson’s as suspect. Inspector Chandler, who was first on the scene, said that in his first interview with John Richardson, the witness had mentioned nothing of his boots. Instead, Chandler said, “He said he came to the back door and looked down to the cellar, to see if all was right, and then went away to his work…he did not go down the steps and did not mention the fact that he sat down on the steps and cut his boot.”

Despite challenges offered by the Inspector and Surgeon, Coroner Wynne Baxter, who conducted the inquest, accepted the testimonies of the three witnesses as an account of the events of the morning.

Profiling the Whitechapel Murderer Following Dark Annie’s Death

The discovery of the second canonical victim led to more speculations as well as further development of how we view Jack the Ripper even in our own time. Dr. Philips speculated from the efficient removal of the uterus that perhaps Annie had been killed for the sole purpose of attaining the organ. This idea was referred to as the “Burke & Hare” theory, a reference to a series of murders committed in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1828 by organ traffickers William Burke and William Hare. Elizabeth Long’s statement that the man she had seen with Annie looked like “a foreigner” fueled this idea. Some thought that the killer was perhaps an American who was selling purloined innards to American medical schools.

Annie’s death also marked the beginning of theorizing that the Whitechapel Murderer had some sort of medical background or was possibly in trade as a butcher. This idea arose from the precision of the uterine removal, and the fact that it must have taken place within a very short period of time. Later medical investigators, however, would put a damper on the image of the Ripper as someone with surgical prowess.

Lastly, Long’s testimony has also supported iconic imagery of the Ripper that lives on into modern times. First, she described the man she saw with Annie Chapman as “shabby genteel”, lending credence to the idea that the man was at least slightly well off. Secondly, her words evoke that famous image of the skulking Whitechapel Murderer in a long coat and hat.

Funeral

The better-heeled members of the Smith family, including her father and sisters, conducted Annie’s funeral in secret on the 14th of September 1888. To avoid the attention of hysterical crowds, the hearse quietly removed her corpse and moved stealthily to the City of London Cemetery (Little Ilford) Sebert Road, Forest Gate, London, E12. Rather than draw attention by using mourning coaches, the family met the hearse at the cemetery.

Annie was buried at public grave 78, square 148. Her body was laid to rest 12 feet down in a communal grave. Since then, the grave has been covered over and the exact location is lost, but in 2008 cemetery authorities marked the approximate location of her grave with a plaque.

Annie Chapman's plaque near her burial location in Manor Park Cemetery.

Cemetery records indicate that a large framed tribute to her was at one time placed near the grave, which read…

“Within this Area lie the Mutilated Remains of Annie Chapman, who was interred here in Grave No. 78 on the 14th of September in the year 1888.”

Sources- Documentary: Jack the Ripper “The Whitechapel Murderer”

- Casebook: Jack the Ripper – Victim: Annie Chapman

- JacktheRipper.co.uk

- “Considerable Doubt” and the Death of Annie Chapman by Wolf Vanderlinden (originally published in Ripper Notes)

- “Windows and Witnesses” by David Yost (originally published in Ripper Notes)

- A Complete History of Jack the Ripper by Philip Sugden